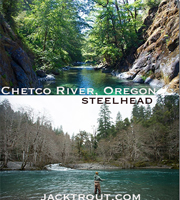

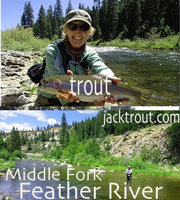

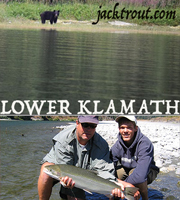

*****DECEMBER & JANUARY STEELHEAD FISHING YIELDS THE LARGEST CATCHES, WE HOPE TO GUIDE YOU!

With Halloween right around the corner Michelle, the girls and I went out to Pappa’s Pumkin Patch outside of the town of Weed. I like the views from their ranch of Mt Shasta.

When Nevada Cement came to town the fish stood up and saluted! I think anytime Mike’s guiding the fish stand up and salute out of respect….

George hooked into Godzomma! Just in time for Halloween.

This guy had teeth that even Crest with its “whitening power” couldn’t help. Now that’s a good picture for you trick-or-treater’s!

This salmon was like trying to reel in a car door with a motor! 25 lbs on a 8 wt fly rod.

Mike hooked up with his customers regularly and after a good fight rowed to the bank to land this beauty.

What a nice healthy steely!

Remember, December & January are big fish months, reserve your dates now. We’re receiving lots of calls. jt

Greg Livingood and fiancee Danielle came up to do a little fly fishing. This was Danielle’s first fly fishing adventure

and on her first hook up she did a great job playing this very large steelhead.

Greg and I were so impressed with Danielle’s first catch ever on a fly rod; A 6lb wild cromer steelhead!

Greg got into the action soon after that and before long he had a smile on his face that said, “I do!”

Right on Greg, you’re living large and good!

Next Greg, Danielle and I head over to the McCloud River in search of terrific dry fly action and colorful brown trout and rainbows.

Greg hooked into a trout at the end of the day on his final cast that was so red.

It was one of the most beautiful rainbows I’ve ever seen, thus coining its name, Little Red Ridinghood.

Wow! I think even Sammy Hagar would be impressed with this fish… (Red.Red, I like Red there’s no substitute for red!)

Dan Brigentino, now there’s a name to remember! 9 years old from Salinas, plays flag football regularly. Loves cheese pizza, chicken drum sticks & fishing with pops! This was Dan’s first time fly fishing, but if you think that was a disadvantage, you’re wrong! Dan set on his fish like a young boy playing Nintendo!

Dan caught this lovely 4lber on our Halloween excursion with his guide Super Rosta!

Tony, Dan’s father got into the action with this hook up.

Nice fish Tony, thanks for coming up, look forward to seeing you with the rest of your boys! jt

Dan it was a hard choice but you are my Sizzler of the Week!

CONGRATULATIONS SIZZLER! JT*****STAY TUNED NEXT WEEK AS WE

POST MORE SUCCESSFUL FISHING PHOTOS!*****

************

THE CALIFORNIA WATER WARS

WATER FLOWING TO FARMS, NOT FISH

Environmentalists lose leverage as agribusiness

locks in cheap, plentiful supplies — for decades

Glen Martin, Chronicle Environment Writer

Sunday, October 23, 2005

After 50 years of legal infighting, a victor has

emerged in California’s water wars —

agriculture.

A decade after environmentalists prevailed in

getting more fresh water down the north

state’s rivers and estuaries to improve fisheries

and wildlife habitat, farmers are again

triumphant. Central Valley irrigation

districts are signing federal contracts that

assure their farms ample water for the next 25

to 50 years.

The Bush administration is driving the trend,

reversing Clinton-era policies that eased

agriculture’s grip on the state’s reservoirs and

aqueducts.

But the Central Valley’s largest irrigation districts have also extended

their influence by mending alliances with the south state’s big urban

water districts, repairing a rupture that environmentalists had exploited.

The ramifications of these developments are evident in strikingly different

places hundreds of miles apart.

In the western San Joaquin Valley, a desert is blooming with cotton and

produce, all sustained with water from California’s northern rivers.

But in the places where this water once flowed — the delta of the

Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, the Trinity River in the far north

state — fisheries have declined drastically. That’s a direct result, biologists

say, of water diversions to the south.

First among the winners of the water wars is the Westlands Water District

southeast of Fresno — the nation’s largest irrigation district.

Pancake flat, this 600,000 acres of arid alkali dirt is one of California’s

most desolate regions.

Yet Westlands is growing riotously: not in homes or shopping malls, but in

melons, tomatoes, almonds, cotton and myriad other crops. Its fields

produced about $1 billion in food and fiber last year.

Depending on who’s doing the counting — agricultural partnerships are

difficult to untangle — Westlands has between 200 and 2,500 farmers.

Though few in number, they command tremendous influence in the local,

state and federal spheres.

“Westlands is politically more powerful than the counties that incorporate

it,” said Barry Nelson, a senior attorney with the Natural Resources

Defense Council, an environmental advocacy group that specializes in

litigation.

Westlands gets its water from the federal Central Valley Project, which

supplies water to a third of California’s cropland and about 50 cities,

including Sacramento, San Jose and several in the East Bay and on the

Peninsula.

The district’s annual allotment of about 1.15 million acre feet — enough to

supply about 2.3 million families — dwarfs those of all other project

participants. The next biggest, the Contra Costa Water District’s, is only

185,000 acre feet.

An acre foot is the amount of water that covers an acre a foot deep.

Now, Westlands and other districts are successfully renewing their

long-term contracts at current levels and at prices far below those paid by

the state’s growing cities, despite protests that pumping large volumes of

water south is killing Northern California’s fisheries.

Westlands is singled out for particular criticism because of its size and the

amount of water it receives, but also because the irrigation of its fields

produces toxic drain water, threatening state waterways. Some critics say

much of its acreage should be taken out of production.

So far, about 200 contracts have been approved, and 80 more are

pending, including Westlands’. About 6 million acre feet of annual water

deliveries is at stake.

Farmers who get federal water are generally charged a fraction of the

free-market rate.

Westlands, for example, pays as little as $31 an acre foot for its federal

water, while the Marin Municipal Water District pays about $500 an acre

foot for water from the Russian River, and Southern California cities pay

$200 an acre foot and up for state project water.

Westlands’ current water contract with the Bureau of Reclamation, the

federal agency that operates the Central Valley Project, runs to 2008.

Barring unforeseen difficulties, agency officials said, approval of the new

contract is expected by mid-February. It will run for 25 years, with an

option for a 25-year renewal.

Opponents say the contract does not acknowledge an extreme

environmental downside. They say Westlands will actually receive

significantly more water than before, at the expense of Northern

California’s rivers.

Because of legislation implemented during the Clinton administration,

Westlands annually received only a percentage of its quota, depending on

the availability of water after meeting water quality standards for San

Francisco Bay and the delta, said Bill Walker, California director of the

Environmental Working Group, an advocacy organization critical of

agricultural subsidies.

Now, he said, the intention of the new contract appears to be the full

delivery of the quota.

In large degree, Westlands’ policies directly reflect the personality of its

dynamic general manager, Tom Birmingham.

Birmingham is unapologetic in his defense of the interests of his

constituents. In particular, he takes deep umbrage at the “demonization” of

his district by environmentalists.

“They’ve become very adept at employing certain words to convey

negative images of us,” Birmingham said during a recent tour of the

district. “Words like ‘large’ and ‘corporate.’ Even our name, Westlands, has

somehow been twisted to convey evil. But those images are totally at odds

with reality.”

Westlands farmers, Birmingham said, have invested heavily in

technology to maximize water conservation and minimize environmental

impacts. He cited several examples:

— Computers meticulously control water and fertilizer output through

drip irrigation lines for thousands of acres.

— Satellite images of fields are regularly consulted to precisely determine

problem areas, resulting in the spot application of pesticides rather than

landscape-scale spraying.

— Irrigation drain water is collected in tiles and recycled to the fields.

If Birmingham is Goliath, his David counterpart is Tom Stokely, a natural

resources planner for Trinity County, 300 miles to the north. Stokely has

long claimed that Westlands’ water demands threaten the once-mighty,

now-struggling salmon runs of the Klamath and Trinity rivers.

Trinity River advocates recently won a court battle against Central

Valley irrigators, resulting in more water releases down the river to

benefit fish. But Stokely questions whether that is enough, given that most

of the river’s water still winds up irrigating cropland.

Federal water from the Trinity and Sacramento rivers flows to the delta,

where it is pumped south.

Birmingham said his district uses no Trinity water, noting that Westlands

water is pumped from the delta to San Luis Reservoir in the winter, when

the primary flow is from the Sacramento River. That water is held in the

reservoir until Westlands irrigators need it later in the year.

But Stokely said the Central Valley Project must be considered as a whole,

with all water held in a theoretical common pot.

And by Westlands taking more water from the delta’s communal water

pot, Stokley said, less is available for the fisheries of the Sacramento River

and its delta, the Trinity River and — indirectly, because the Trinity is a

tributary — the Klamath River.

“The Trinity River is more than an important salmon stream in its own

right,” Stokley said. “It’s the cold water supply for the Klamath and the

Sacramento. Without cold water, salmon die. And it’s the essential clean

water supply for the delta. By locking up 1.2 million acre feet of CVP water

a year, Westlands diminishes the availability of Trinity water in general.”

The triumph of Big Agriculture is especially bitter to conservationists

because it follows more than a decade of federal legislative moves designed

to divide the state’s available water in an equitable fashion among

farmers, cities and the environment.

A key landmark was the 1992 federal Central Valley Project

Improvement Act, designed to end the litigation that had characterized

California’s water politics for decades.

The act empowered a joint state and federal agency, CalFed, to embark on

an ambitious program of environmental restoration in the Central Valley,

the delta and San Francisco Bay. It also provided for a significant amount

of fresh water to revitalize the beleaguered delta and bay. About 800,000

acre feet of water were earmarked for the delta.

But under the Bush administration, this era of cooperation stuttered, then

reversed.

In 2003, CalFed brokered a deal with state and federal project managers

and water contractors known as the Napa agreement, providing for

greater water exports from the delta, where both the state and federal

pumps are located.

Westlands would benefit significantly from the Napa accord in that the

agreement would assure stable, large-scale water deliveries to the huge

district.

But environmentalists sued to stop the operations plan, claiming the

agreement undermines the essential intent of the Central Valley Project

Improvement Act: Increased freshwater flows through the delta and bay.

Tupper Hull, a spokesman for Westlands, said the district’s analysis of the

Napa agreement’s operations plan indicates it will not degrade

environmental protections.

“This plan will allow the pumps to shut down when there is a threat to the

fish and run high when there is no jeopardy,” Hull said.

This month, a state appeals court ruled that CalFed’s environmental

documentation on its current programs is inadequate, because the agency

didn’t fully consider reducing water exports to Southern California.

A few years ago, Westlands was alienated from the state’s urban water

districts. At that time, it was unclear where the water would come from

for environmental restoration, and municipal water districts and

environmentalists had established tentative alliances against large

Central Valley irrigators.

Today, the situation is reversed.

“A couple of years ago, I was at loggerheads with Westlands,” said Tim

Quinn, the vice president for state water project resources for the

Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. The district serves 18

million customers and consumes about 1.9 million acre feet of water

annually, most of it from the state water project.

Quinn said Westlands was known for playing hardball in the not-so-distant

past — litigating any government agency decision it didn’t like, claiming

water held by other districts.

“But in recent years, there have been profound changes at Westlands,”

Quinn said. “They’ve moved to the center.”

Birmingham, he said, “is showing real skill at pounding out centrist

solutions.”

Westlands critics say the Metropolitan Water District’s turnaround can be

explained by expedience. The district, they say, is buying water on the

open market from agricultural districts; the water interests of big farms

and big cities are thus congruent as never before.

“The recent trend of ever-increasing water exports south of the delta is

basically benefiting huge water districts, both agricultural and urban,”

said Hal Candee, a senior attorney for the Natural Resources Defense

Council.

Battered though they may be, environmentalists have not given up the

fight. The defense council and its allies are expected to sue to block the new

Westlands contract if, as expected, it is approved.

Opponents to the contract were heartened by a recent decision issued by

U.S. District Judge Lawrence Karlton declaring water contract renewals

for eastern San Joaquin Valley farmers illegal because of possible

violations of the Endangered Species Act.

East valley farmers get water from Friant Dam on the San Joaquin River.

After the dam went up in the 1940s, the San Joaquin essentially dried up,

and its once-robust salmon runs disappeared.

“The Friant contracts set a precedent for all other contracts, including

Westlands,” said Candee, who filed the suit for the Natural Resources

Defense Council.

If Birmingham is worried about the upcoming contract, he doesn’t show it.

Touring his district, surveying its lush crops, he projects nothing but

confidence.

“When I took over as manager in 2000, we were getting about 50 percent

of our allotment from the CVP,” he said. “Now we’re getting about 75

percent in most years, and this year we received 90 percent.

“Our relationships with the agencies are improving, and our water

supplies are improving. We’re doing what we’ve always done — putting our

water to reasonable and beneficial use as required by our federal contracts,

and producing crops of incredibly high value.”

Westlands Water District

Size: 600,000 acres.

Number of farms: 600.

Number of working farmers: 200 to 2,500, depending on sources.

Environmentalists claim lower numbers; Westlands staffers stand by the

higher figures.

Crops: Westlands produces more than 60 food and fiber crops, including

almonds, pistachios, cotton, melons, lettuce and alfalfa. It is also an

important dairy region.

Annual gross revenues: About $1 billion.

Amount of water used: Westlands has a contract with the U.S. Bureau of

Reclamation for 1.2 million acre feet of water annually. It buys extra

water ó less than 100,000 acre feet ó from other districts.

Delivery system: Westlands gets its water from the federal Central Valley

Project. Water is pumped from the delta to San Luis Reservoir through the

Delta-Mendota Canal, and from there it is delivered to Westlands through

the San Luis and Coalinga canals. Water is then delivered to district

farmers through 1,034 miles of underground pipe.

The controversy: Environmentalists claim fisheries and wildlife in San

Francisco Bay and the delta of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers are

being hurt by excessive water exports to the western San Joaquin Valley,

especially Westlands.

Where Westlands water comes from

1. Water from north state reservoirs ó Shasta Lake on the upper

Sacramento River and Trinity Lake on the Trinity River ó is sent

southward, down the Sacramento River.

2. After entering the delta, the water is pumped to San Luis Reservoir and

from there to Westlands.

3. The Westlands Water District has a federal contract for about 1.2

million acre feet of water delivered annually, or about 20 percent of the

capacity of the Central Valley Project.

E-mail Glen Martin at glenmartin@sfchronicle.com.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Klamath Restoration Council

Our mission is to restore and protect the uniquely diverse ecosystem

and promote the sustainable management of natural resources in the entire Klamath River

watershed.

Mt. Shasta Ski Park

Mt. Shasta Ski Park Shasta.com - Northern CA's premiere business website!

Shasta.com - Northern CA's premiere business website!

WEED ALES & BREWERY

WEED ALES & BREWERY

EASTER ISLAND INFORMATION & TOURISM SITE

CHILE!!

EASTER ISLAND INFORMATION & TOURISM SITE

CHILE!!