*****HAPPY HOLIDAYS! CHILE RIGHT AROUND THE CORNER * STEELHEAD FISHING WILL BE GOOD AFTER THIS NEXT RAIN * I HAVE OPENINGS FOR DEC 18TH THROUGH DEC 23RD!!*****

The greatest lenticular cloud ever!

This is Michelle my girlfriend. She and her mother, Jodie, opened the Best Little Hair House, located at 155 Main Street in Weed, California. 530-938-1845

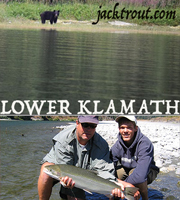

Leonard and Joaquin Santana visited us this past week and enjoyed their adventure on the Klamath. Right off the bat, Leonard hooked into two monsters and fought the second one

like he had done this before–even though he never had! Joaquin cheered his father on as he was on a visit himself from Stockholm, Sweden.

What’s better during the holidays than to be out with dad on the river catching steelhead and sharing memories together

Wow! What a prize for a first catch, POPS! CONGRATULATIONS, YOU’RE MY SIZZLER OF THE WEEK AWARD WINNER! JACK TROUT

I’ve noticed this year so many of the steelhead we’re catching are wild!

As we looked down river, we could see the Klamathon Bridge up ahead of us which signaled the day was near end. I glanced over to look at the billy goats that are always eating willows and playing along the banks of the river. I noticed a goat tied up in the fencing that looked to be not moving…. I rowed nearer, and saw a back leg move. I went to shore with my hemostats and began untangling horns, legs, and knotted twine.

At first the goat panicked when I got close but completely calmed down as soon as I began cutting the fencing away and talking to the friendly animal. This goat was so lucky–we were the only people on the river that day. It was 36 degrees and 15 minutes from dark. It felt so good to save this goat’s life, catch 14 steelhead and meet Leonard and Joaquin. What a great day indeed! I had that Elton John’s song in my head; Someone saved my life tonight, Sugar Bear! Sweet freedom whispered in my ear! Yea that’s what life’s about, I felt so damn proud of saving that goat’s life it made me think that Shasta Dog must have been watching, smiling, wagging that tail of hers.

Joaquin was quite humored by the whole event and later I found an apple and we fed the poor dehydrated ram. After about 5 minutes she was like one of the tribe. I named her Mrs. Griffith!

A minute later Oreo came by to take a few bites of the apple.

These were some very nice goats difinitely worth visiting again

(not tied up).

Hello Jack

I don’t want to get into a pissing contest but we have some steelheads in the east as well.

This one was caught today on ther Salmon River in Pulaski,N.Y. I was not the fisher.

Enjoy your photos.

Laurie Swinghammer

Hudson Quebec

To my two best friends in the world: Shasta and Lambchop. It hurt to lose both of you this year but you’ll never be forgotten. Thanks for the great memories and companionship. You’re in my thoughts this holiday season. Thank you for watching my weblog. Sorry to Jack Taylor and Jim Mossop, the pictures on the Trinity and the Klamath were too big to use. I’m buying Photo Suite 7 and I’ll have them up for the next story! Many Rivers To You, Jack Trout

OTHER NOTES:

Restore the Klamath. Fix the World.

Klamath Restoration Council News and Information Network

htt://www.pelicannetwork.net/krc.htm

Posted by Zeke Grader

http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/g/a/2005/12/14/gree.DTL

GREEN Salmon Season

In the Northwest, the fish is of huge economic importance,

which is perhaps the only reason there are any left

Gregory Dicum, Special to SF Gate

Wednesday, December 13, 2005

With winter rains arriving, the region’s rivers and streams are swelling. In

Marin, the increased flow in streams like Lagunitas Creek allows one of the

world’s most magnificent natural cycles — the return of the salmon — to

unfold as it has for millennia.

Narrow streams are starting to be filled with improbably big, red fish, back

in their home waters after three years at sea, fat and ready to breed. In

the midst of our self-absorbed human world, wild nature can still find a way

to hang on. Each year’s return of these fish is a sign of hope, but also a

reminder of how close we are to irreversibly damaging the world around us.

“The most important lesson in ecology is: Everything’s connected,” says

Todd Steiner, director of Salmon Protection & Watershed Network, an

organization that works to protect salmon in the Lagunitas watershed,

which comprises 103 square miles in West Marin, from Woodacre to

Tomales Bay. “We’re trying to repair natural processes by taking a

watershed approach.”

SPAWN employs a combination of research (Steiner is a wildlife biologist by

training), habitat restoration, lobbying, education (including guided public

salmon viewing) and litigation — a microcosm of the activity surrounding

salmon from California to Alaska.

Salmon restoration requires such a multifaceted tool kit because the fish’s

life cycle is so complex, linking land and sea. Each year, baby salmon hatch

in freshwater streams throughout the West. They move downriver as they

grow, before finally transforming themselves into ocean fish.

Several years later (the timing depends on the species), they return to the

exact same stream they were born in and make the arduous journey up to

the headwaters. There, they pair up and spawn in gravel nests before

expiring, exhausted.

The oldest known salmon fossil, from British Columbia, is about 50 million

years old, making this fish a vital part of ocean and terrestrial ecosystems.

“Through the evolutionary process they’re specific to the local conditions —

water temperature, water chemistry, when rainfall happens and so on,”

says Steiner. “They’re all adapted specifically to their location.”

While the thousand endangered coho salmon in Lagunitas Creek don’t go

more than a few miles inland, the nearly two million chinook salmon that

swim through the Golden Gate and into the Sacramento River go hundreds

of miles, into the Sierra foothills and, before the Shasta Dam was completed

in 1945, all the way to Shasta.

The Sacramento is the second-largest salmon-producing river in the lower

48 and is home to nine-tenths of California salmon, despite the loss of 90

percent of its salmon habitat by the 1970s. Salmon are a defining part of

nature here.

“These fish have been important in both the nutritional and spiritual

sustenance of people in the Northwest forever,” Steiner points out, “– as

long as there have been people.”

And modern people in this place are no different: Salmon are of huge

economic importance, which may be the only reason any are left. Salmon

conservation efforts on the Klamath River go back at least to the 1890s.

Fifty years ago, salmon fishermen, seeing the decline of the salmon fishery

in San Francisco Bay, organized and began to call for more comprehensive

conservation measures.

“With salmon, you get involved with just about every possible environmental

issue,” says Zeke Grader, the San Francisco-based executive director of

the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations.

“I never thought about that when I started doing this 30 years ago, but to

try and protect those fish that our members rely on we’ve worked on

everything from water diversions to dam operations to gravel mining to

pesticides to genetically modified organisms — you name it. I thought,

‘Thank God, at least we don’t have to get involved in air quality issues,’ but

now we’re finding that between mercury deposition in the ocean and

carbon sequestration that we have to start paying attention to that too.”

Mercury released into the air by coal-fired power plants rains into the sea,

where it can accumulate in fish. Eventually it makes its way into the bodies

of people who eat the fish, where it can cause illness.

Grader, whose father was a salmon fisherman and who grew up working in

salmon processing plants, says that salmon fishing is a threatened way of

life. There’s been a decrease of 80 percent in the number of salmon fishing

permits in the past two decades, with fewer than a thousand currently in

California. Each one represents a local small business directly dependent on

a healthy environment.

But now they’re up against agribusiness too. In the past decade, a handful

of Scandinavian multinationals have been setting up salmon farming

operations around the world. Originally a response to exterminated wild

stocks in Norway, these cookie-cutter operations now churn out fish in

British Columbia, Chile and elsewhere. (Salmon farms are not allowed in

California, Oregon and Alaska.)

Farmed fish typically sell for half the price of wild salmon, seriously

threatening the fishermen’s livelihoods. Worse, farmed salmon also threaten

wild fish populations.

“It’s like industrial-scale beef or pig feedlots,” says Sophika Kostyniuk, the

California markets campaigner at the Coastal Alliance for Aquaculture

Reform. “There’s a tremendous concentration of animals being raised in a

small area. They’re fed antibiotics and pesticides if there’s an outbreak of

disease.”

The diseases fostered in these floating nets filled with fish can pass to

nearby wild fish. Worse, farmed fish can escape.

Kostyniuk says that in July more than a million fish escaped during a single

storm in Chile. “Chile didn’t even have an indigenous salmon population,”

adds Kostyniuk, “but now they do.” The invasive Atlantic salmon threaten to

disrupt Chilean river ecosystems, with unknown consequences for native

species.

In places like British Columbia that do have native salmon, farm fugitives,

which are mostly of Atlantic stock, displace the natives that are so finely

tuned to local ecosystems. Juvenile Atlantic salmon have now been found in

Alaskan streams, hundreds of miles from the nearest fish farms in Canada.

Because salmon farming is driven by consumer demand, says Kostyniuk, this

is an area where consumer choice can have instant environmental benefit.

“The most important thing consumers need to do,” she says, “is question

why this fish is being offered to them so cheaply.”

Though CAAR is based in British Columbia, Kostyniuk is in San Francisco

because California is that province’s major farmed-salmon market. More

than 60 percent of the salmon sold in the United States was farmed in

British Columbia or Chile.

“We always encourage people to ask questions to find out where their

salmon is coming from,” says Kostyniuk in her sensible-sounding Canadian

accent. “Just ask in your restaurant or grocery store if it’s wild or farmed.

… I’ve been working on this issue for three years in the Bay Area, and I’ve

just seen such a change in public consciousness of the issue.”

Most recently, the issue has been picked up by chefs around the country.

“Just like vegetables are seasonal, so are fish,” says Chris Cosentino, chef

at Noe Valley’s Incanto. “If it’s in season that’s when it’s at its best — it’s

pretty logical.”

Cosentino notes with disgust that farmed fish are fed dyes to make their

flesh pink. “We serve only local wild salmon,” he adds.

But this year has seen a double whammy for local salmon fishermen. On top

of all their other woes, catches were severely restricted because of

disastrously low salmon populations on the Klamath River three years ago.

The fish were caught in a political battle in which the Bush administration

overallocated the Klamath’s water to farmers, allowing the young fish in the

river to die.

“We got really whacked on our salmon season,” says Grader, the

Fishermen’s representative. “What should have been a very good salmon

season was a bleak one. We figure the losses may have reached or

exceeded $100 million, and it doesn’t look good for the next two years.”

“The tribes on the Klamath really got screwed,” he adds, his voice cracking

slightly. “The pain up there was just tragic.”

In view of these kinds of challenges, every native salmon happily spawning

in the place it was born is a small environmental victory, something that is

not lost on Grader. “Actually things look good in a lot of ways, compared to

the things we’ve been up against,” he says. “What needs to be done is

known. It’s a matter of political will.”

Steiner has faced the same thing in Marin, and the rebounding coho stocks

in the Lagunitas watershed give him hope. “We use the salmon as our

totem species,” he says. “These endangered species are the canary in the

coal mine. The things that we do to protect them protect my children who

play in the creek, and protect the health of the community in general.”

###

http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/local/252001_salmon14.html

Suit wants hatchery fish counted in runs

Wednesday, December 14, 2005 By LISA STIFFLER

SEATTLE POST-INTELLIGENCER REPORTER

Are salmon born in plastic trays the same as those hatched in streambeds?

Absolutely — if you’re part of a coalition of farmers and property rights and

business groups.

No way — if you’re an environmentalist.

And if you’re the government agency responsible for saving vanishing West

Coast salmon runs, the answer is this: Both have value, but they aren’t

created equal.

That debate triggered a lawsuit filed Tuesday in U.S. District Court in

Eugene, Ore., by the Pacific Legal Foundation, a California-based property

rights group.

The suit seeks to have the National Marine Fisheries Service add hatchery

fish to wild populations when considering the health of salmon runs.

Sixteen runs in Washington, Oregon, California and Idaho are protected

under the Endangered Species Act. They include Puget Sound chinook.

“These current listings are illegal,” said Russell Brooks, lead attorney for

the plaintiffs. “We expect the judge to rule that they are illegal and order

that when (the Fisheries Service) goes back and reviews the population

that they must consider all the salmon.”

If that were so, none of the runs would receive federal protection, said

Fisheries Service spokesman Brian Gorman.

Without that protection, restrictions on streamside development could be

weakened, fishing levels increased and limits on pesticide use near

waterways relaxed.

This summer, Earthjustice, an environmental law firm, filed a suit in U.S.

District Court in Seattle challenging a federal policy that looks at wild and

hatchery fish when sizing up their likelihood of survival. Last month, a judge

refused to dismiss the suit, as requested by the Justice Department.

The Pacific Legal Foundation won a ruling in 2001 by U.S. District Judge

Michael Hogan in Eugene that required fishery managers to consider

hatchery salmon numbers when determining whether to list wild stocks as

threatened or endangered.

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have

expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.

Klamath Restoration Council has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is

PelicanNetwork endorsed or sponsored by the originator.)

Klamath Restoration Council

Our mission is to restore and protect the uniquely diverse ecosystem

and promote the sustainable management of natural resources in the entire Klamath River

watershed.

We believe this will be accomplished with actions and legislation that integrate sound and

proven techniques based on tribal knowledge, local experience and the best of Western Science.

http://www.pelicannetwork.net/krc.htm

Mail: Box 214 Salmon River Outpost Somes Bar, CA 95568 Phone: 530 627 3054

Contact: Jack Ellwanger, Klamath Restoration Council Networker

Created by: http://www.pelicannetwork.net/

Mt. Shasta Ski Park

Mt. Shasta Ski Park Shasta.com - Northern CA's premiere business website!

Shasta.com - Northern CA's premiere business website!

WEED ALES & BREWERY

WEED ALES & BREWERY

EASTER ISLAND INFORMATION & TOURISM SITE

CHILE!!

EASTER ISLAND INFORMATION & TOURISM SITE

CHILE!!